I just finished listening to the book Moloka’i by Alan Brennert. The story follows the life of a Hawaiian woman who contracts leprosy at age 6. It illustrates the upheaval to her life and her family along with radical changes occurring in Hawaii from the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries.

I know much of the islands’ history and was pleased to hear it described from a sympathetic perspective, particularly:

- The way that missionaries and foreigners treated the Hawaiian people with condescension, while attempting to annihilate their culture and language

- How leprosy (among other diseases) decimated the native community and tore apart families

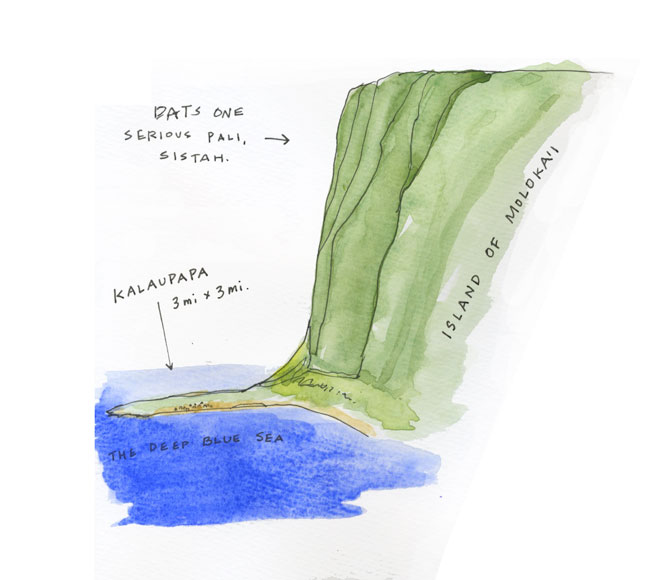

- The banishment of leprosy victims to the remote peninsula of Kalaupapa on Moloka’i

- The death of King Kalakaua

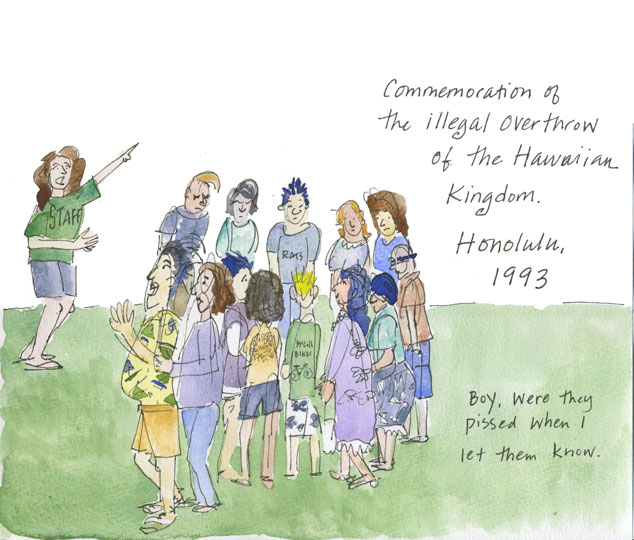

- The illegal overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy by a bunch of American businessmen (after the January 6 insurrection, this became very real to me) and Queen Liliuokalani’s subsequent imprisonment

- The bombing of Pearl Harbor

- The Mainland imprisonment of Japanese Americans

- The emergence of many technologies like air travel and motion pictures

Other memorable details include fictional interactions with Father Damien. Damien is historically written as a hero: someone who came to lawless Kalaupapa and imposed order and civilization. In the book, he’s a religious zealot (one of those “my way (salvation) or the highway (Hell)” guys) and I realize that he was; he may have brought some needed management but I can no longer think of him as a factor only for good.

The victims were all treated like criminals—shunned by their families and society, banished and basically imprisoned. Many died so fast that their graves remain unmarked. The Christians on the peninsula were heavy-handed in the way they treated the patients, e.g. in the book, they don’t allow the girl to live with her only family in the settlement, her Uncle and his lover (also patients), because they “feared for her safety” being out in the community. Instead she’s forced to live with the nuns and is raised by them.

But I digress. Listening to the book brought back flashes of my own visit in 1990. I had joined a weekend Sierra Club service trip to help clear some of the many unmarked graves. We flew from Honolulu to Kaunakakai and then in a puddle jumper to that apron of land bordered by dramatic, vertical pali (ridges) and the Pacific ocean itself. Were it not for its terrible past, the place might be considered a remote paradise. Kalaupapa is now a national historical site.

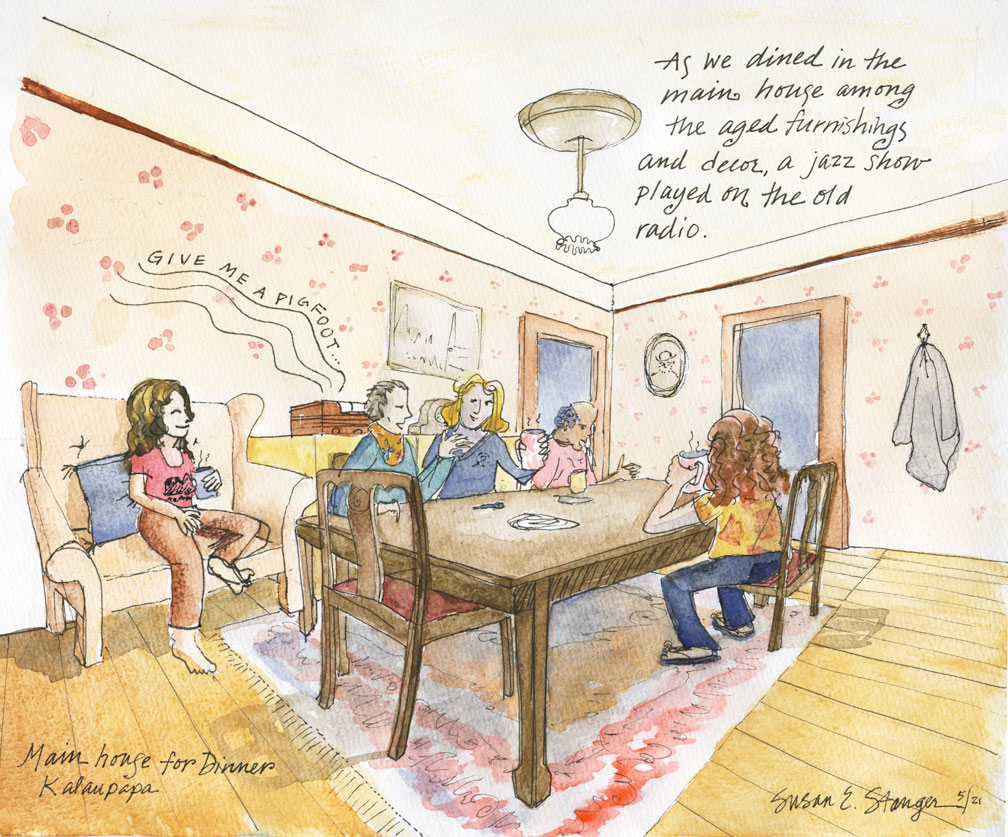

It was like the town that time forgot, with cars from the 40’s and 50’s, dirt roads, limited electricity and only a few residents. When the cure for Hansen’s disease was finally discovered, some patients at the settlement decided to stay in the community rather than live out in the world with their disfigurement and the stigma attached to it. We stayed in the Parks Service bunk house and ate our meals as picnics or in the main house. It was strikingly beautiful and HOT as there are many harsh, open areas. The work was hard but satisfying and during our break, we explored the coast.

By Sunday afternoon, the fog had rolled in and stubbornly refused to leave, meaning that our flight out was canceled and we were staying another night. I was secretly thrilled, but my manager at Hawaiian Graphics was less so—when I called to say I wasn’t able to report to work the following day, she was pretty cranky about it (I think she was jealous).

That chilly evening, Kalaupapa was enveloped in mist and a spirit of bygone days. As we dined in the main house among the aged furnishings and décor, a show playing old jazz from Honolulu sputtered through the radio, the sound waves remarkably crossing the 26-mile Ka’iwi channel between the islands, adding to the mystery of the night. This is what I remember most about that trip to Kalaupapa—the feeling of a time warp in a place that time forgot.

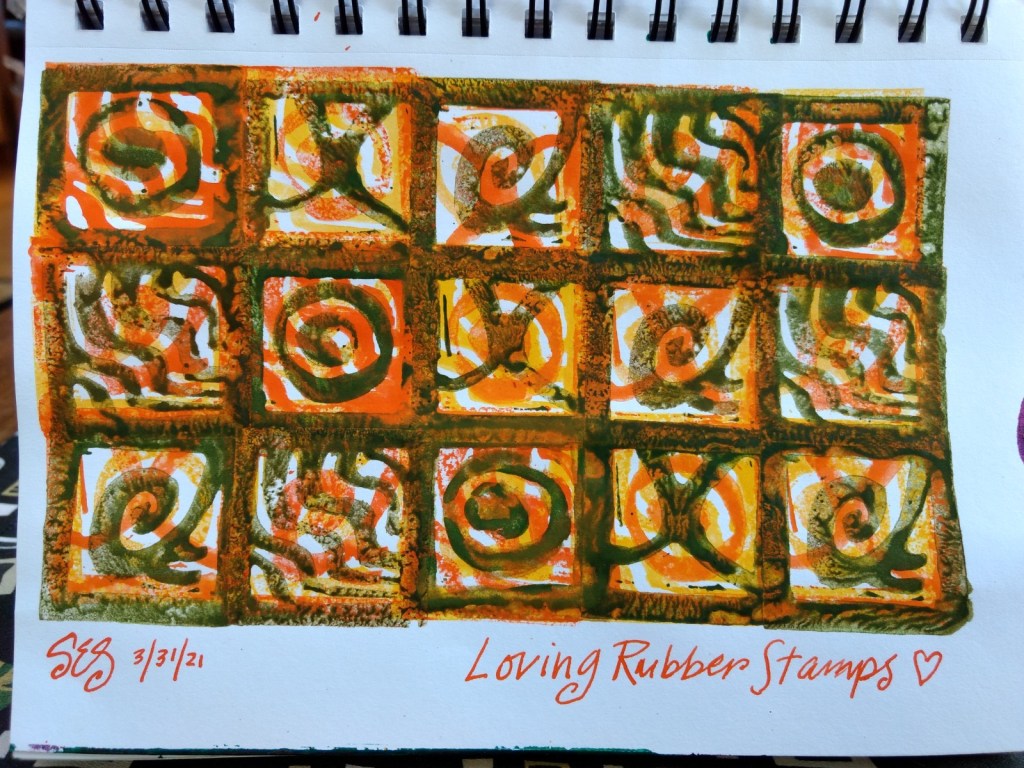

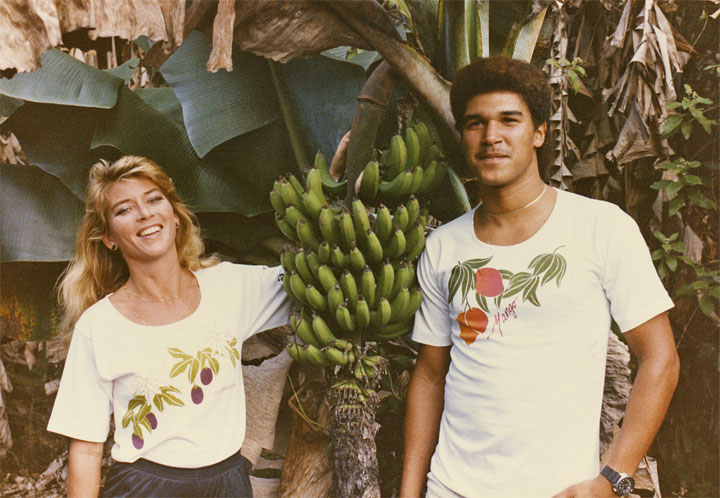

In my first major entrepreneurial venture, Red Ginger, I designed and sold T-shirts, which I printed in my garage. At the time, my technique was to cut the drawing and lettering through a thin layer of laquer film that was stuck to acetate. After peeling off the positive areas, I adhered the laquer (with a nasty chemical) to the screen, removed the acetate and then squeegeed the ink through to the fabric. I had to use an x-acto knife as my primary tool (not quite as bad as using your finger as a stylus, but you get the idea).

In my first major entrepreneurial venture, Red Ginger, I designed and sold T-shirts, which I printed in my garage. At the time, my technique was to cut the drawing and lettering through a thin layer of laquer film that was stuck to acetate. After peeling off the positive areas, I adhered the laquer (with a nasty chemical) to the screen, removed the acetate and then squeegeed the ink through to the fabric. I had to use an x-acto knife as my primary tool (not quite as bad as using your finger as a stylus, but you get the idea).

Stay safe everyone!

Stay safe everyone!

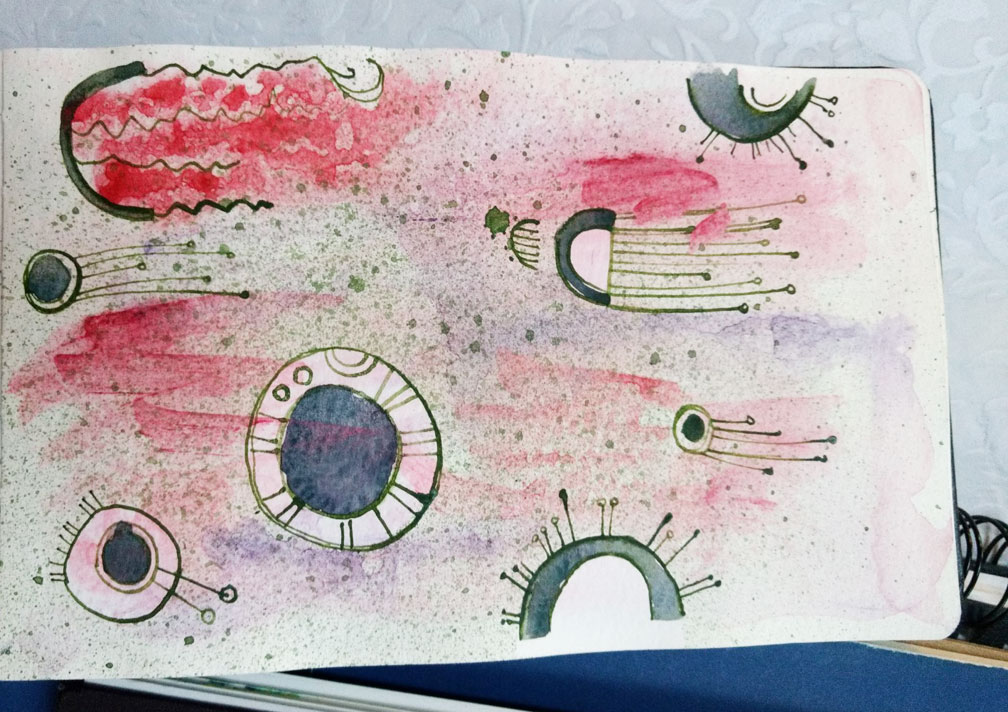

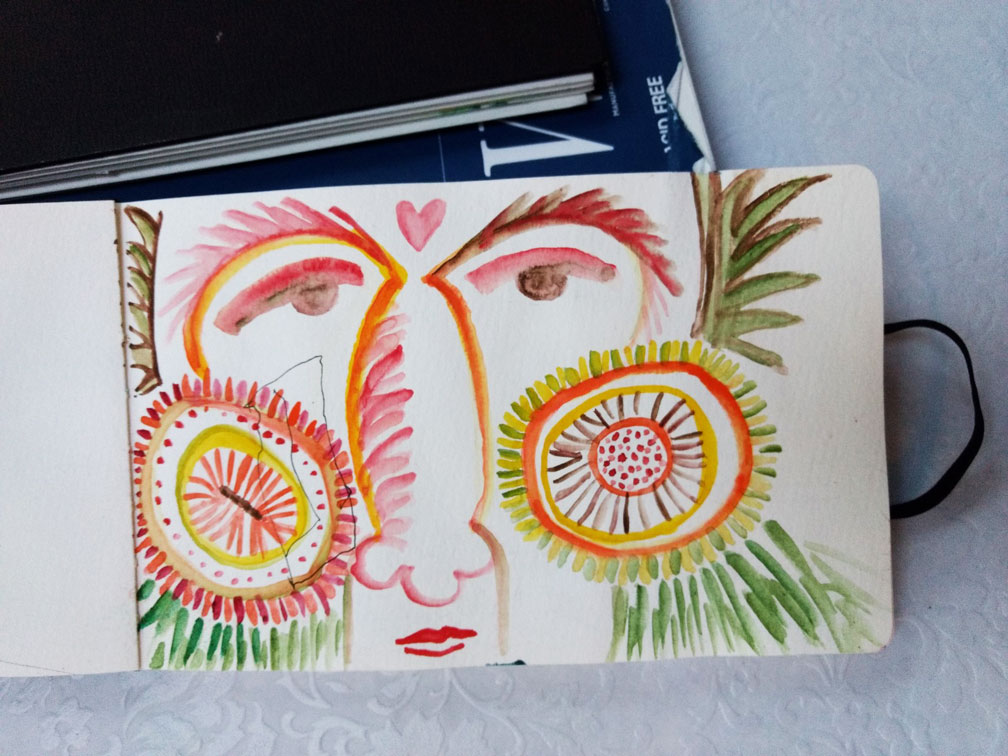

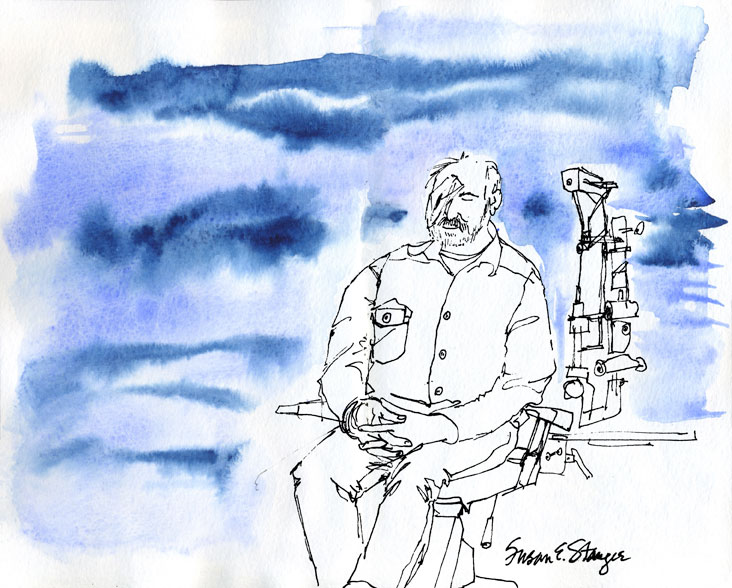

We got to know most of the doctors at the UCSF Ophthalmology department. With nothing to do but worry, I kept myself busy during the appointments by sketching.

We got to know most of the doctors at the UCSF Ophthalmology department. With nothing to do but worry, I kept myself busy during the appointments by sketching.

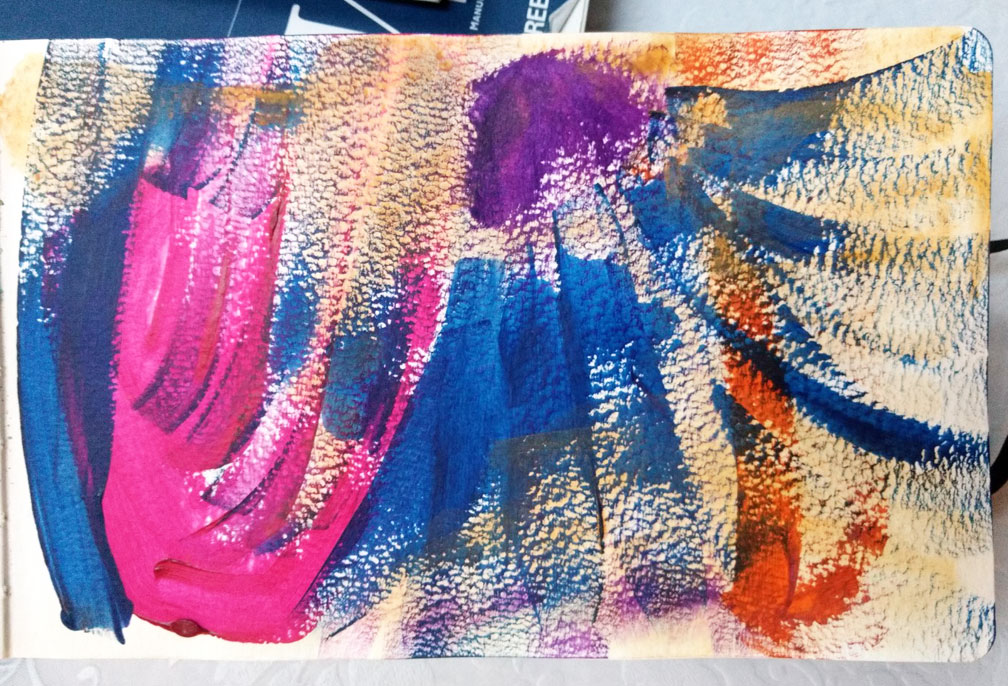

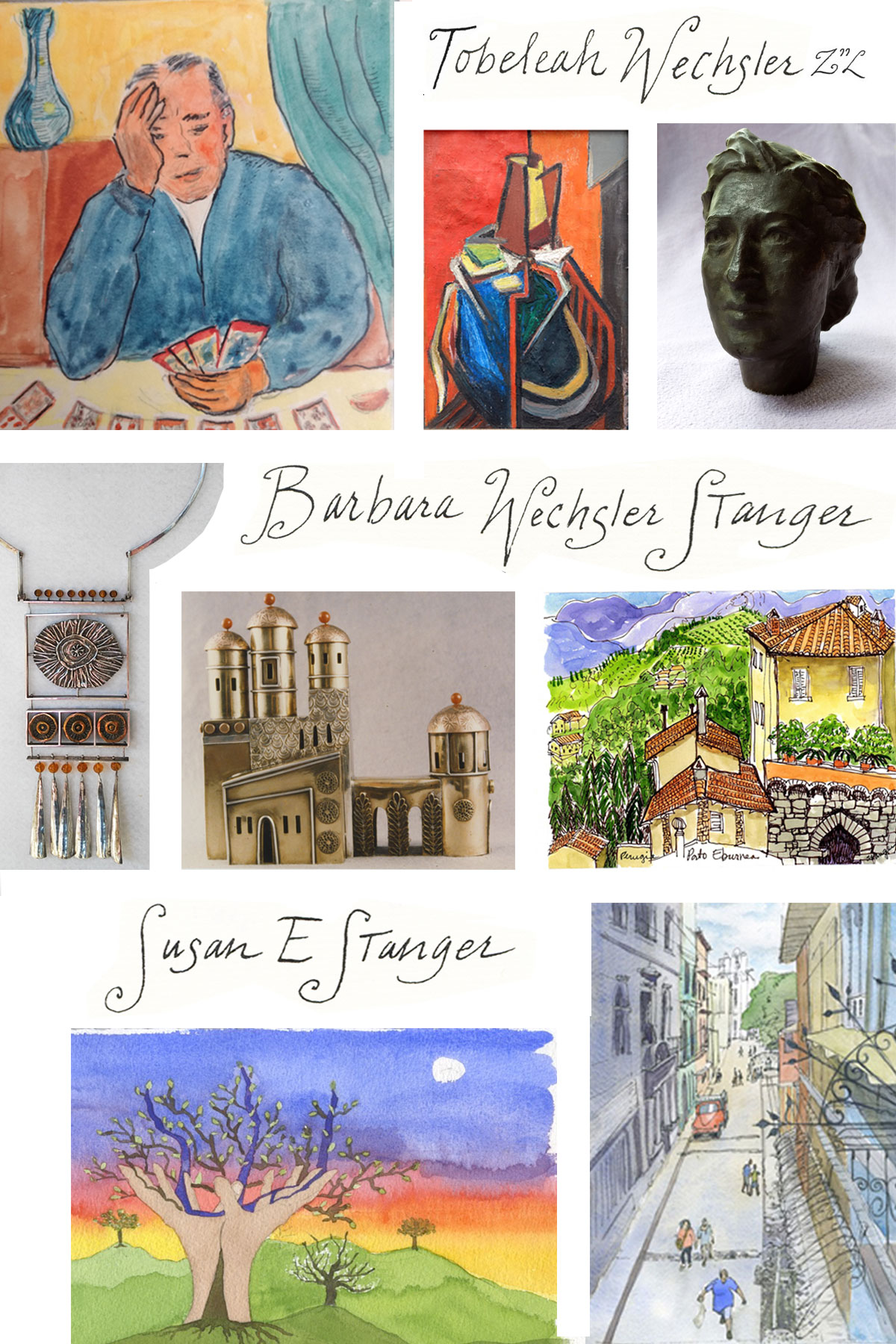

Le-dor va-dor means “From Generation to Generation.” It expresses the directive to teach your children the culture, values and lessons of Judaism. In our case, the teachings included art! My grandmother was a painter and sculptor, my mother is a metalsmith, ceramist and one who draws. I’m a sketcher and painter. Together, our work will span over a hundred years of art in one family.

Le-dor va-dor means “From Generation to Generation.” It expresses the directive to teach your children the culture, values and lessons of Judaism. In our case, the teachings included art! My grandmother was a painter and sculptor, my mother is a metalsmith, ceramist and one who draws. I’m a sketcher and painter. Together, our work will span over a hundred years of art in one family.

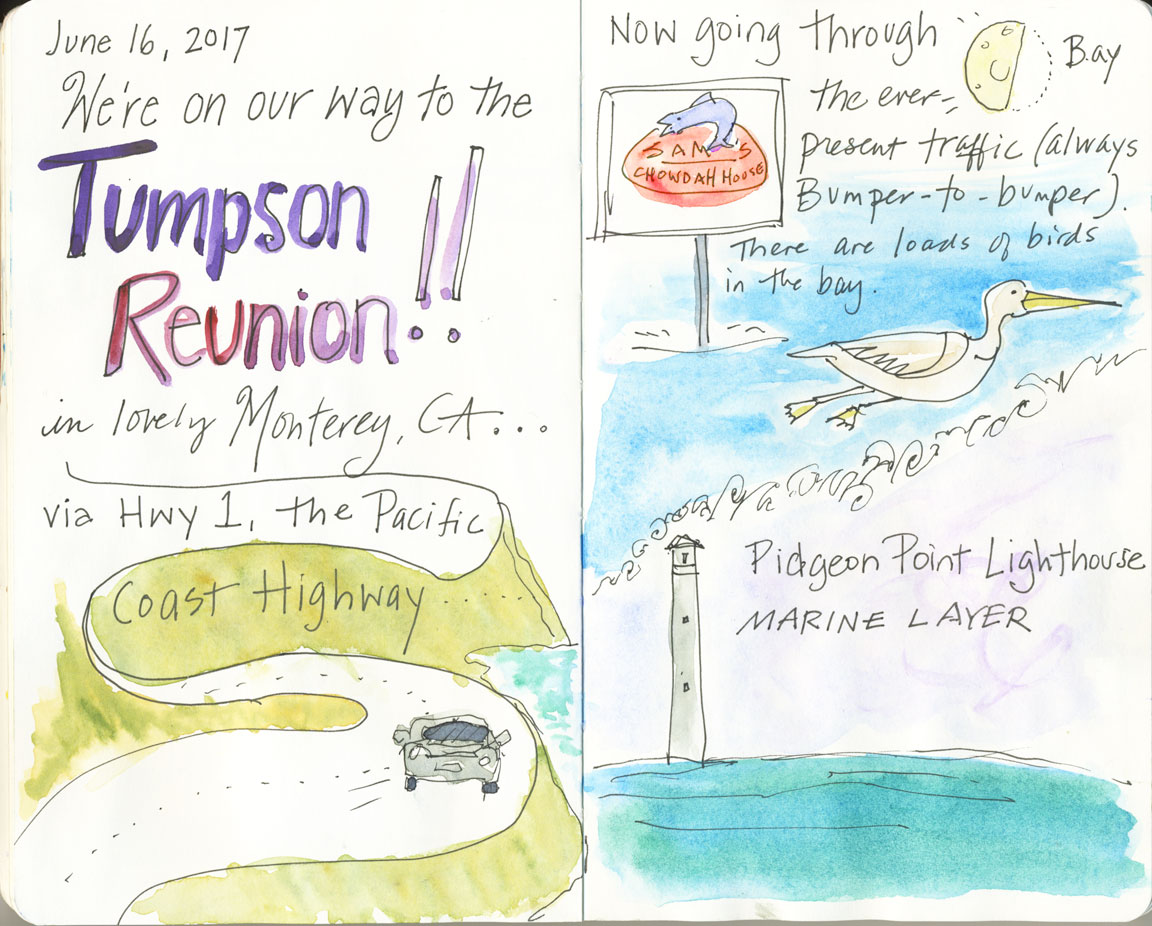

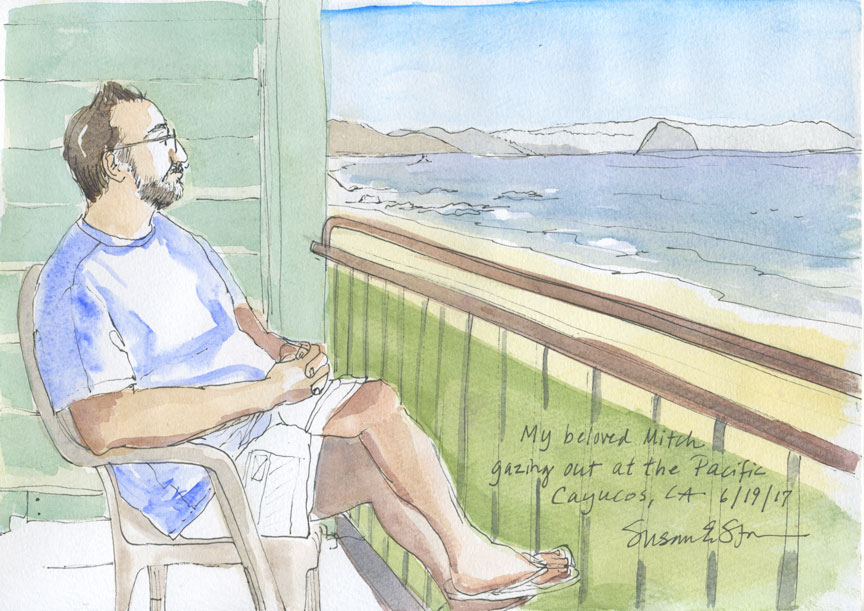

We drove down on Friday and ran into traffic in Half Moon Bay and Santa Cruz, of course. It’s still so beautiful on the coast. We were blessed with incredible weather, sunshine and not too much wind.

We drove down on Friday and ran into traffic in Half Moon Bay and Santa Cruz, of course. It’s still so beautiful on the coast. We were blessed with incredible weather, sunshine and not too much wind.